Findings

This page highlights only few of our findings. Please explore our Publications for a comprehensive overview of our extensive research.

Ebb and Flow of Mental Health Throughout College Years

Understanding the dynamics of mental health among undergraduate students across the college years is of critical importance, particularly during a global pandemic. In our study, we track two cohorts of first-year students at Dartmouth College for four years, both on and off campus, creating the longest longitudinal mobile sensing study to date. Using passive sensor data, surveys, and interviews, we capture changing behaviors before, during, and after the COVID-19 pandemic subsides. Our findings reveal the pandemic's impact on students' mental health, gender based behavioral differences, impact of changing living conditions and evidence of persistent behavioral patterns as the pandemic subsides. We observe that while some behaviors return to normal, others remain elevated. Tracking over 200 undergraduate students from high school to graduation, our study provides invaluable insights into changing behaviors, resilience and mental health in college life. Conducting a long-term study with frequent phone OS updates poses significant challenges for mobile sensing apps, data completeness and compliance. Our results offer new insights for Human-Computer Interaction researchers, educators and administrators regarding college life pressures.

The dataset used in this paper has been released for public use. This is the longest mobile sensing data to date looking into mental health and behavior of college students over 4 years. We hope this dataset will be useful in advancing research into the mental health of college students.

Explore the Full Research College Experience Study DatasetFirst Gen Lens

The transition from high school to college is a taxing time for young adults. New students arriving on campus navigate a myriad of challenges centered around adapting to new living situations, financial needs, academic pressures and social demands. First-year students need to gain new skills and strategies to cope with these new demands in order to make good decisions, ease their transition to independent living and ultimately succeed. In general, first-generation students are less prepared when they enter college in comparison to non-first-generation students. This presents additional challenges for first-generation students to overcome and be successful during their college years. We study first-year students through the lens of mobile phone sensing across their first year at college, including all academic terms and breaks. We collect longitudinal mobile sensing data for N=180 first-year college students, where 27 of the students are first-generation, representing 15% of the study cohort and representative of the number of first-generation students admitted each year at the study institution, Dartmouth College. We discuss risk factors, behavioral patterns and mental health of first-generation and non-first-generation students. We propose a deep learning model that accurately predicts the mental health of first-generation students by taking into account important distinguishing behavioral factors of first-generation students. Our study, which uses the StudentLife app, offers data-informed insights that could be used to identify struggling students and provide new forms of phone-based interventions with the goal of keeping students on track.

Explore the Full ResearchImpact of COVID-19 Pandemic on Mental Health and Behavior of College Students

Study #1: We conducted one of the earliest studies that used mobile sensing and ecological momentary assessments to determine the impact on mental health and behaviors during the COVID-19 pandemic. This study provides preliminary insight into mental health and related behaviors during the initial phases of the COVID-19 pandemic. Depression, anxiety, and sedentary time increased as the COVID-19 pandemic encroached on a college campus in parallel with large-scale policy changes. Using a mixed linear model of smartphone mobile sensing and self-reported mental health questions, we were able to infer the proportion of COVID-19–related news stories; moreover, we could validate that participants’ mental health and related behaviors changed in lockstep with increased media coverage and proximity of the pandemic. For these college students, the early days of the pandemic coincided with what is typically a time of increased time and depression, and we observed altered behavioral patterns and a decrease in mental health above and beyond typical academic terms. Explore the Full Research

Study #2: In a follow-up study, we tried to understand the behavioral and mental health impacts associated with the COVID-19 pandemic, measured by interest across the United States in the search terms coronavirus and COVID fatigue. Linear mixed models demonstrated differences in phone use, sleep, sedentary time and number of locations visited associated with the COVID-19 pandemic. In further models, these behaviors were strongly associated with increased interest in COVID fatigue. When mental health metrics (eg, depression and anxiety) were added to the previous measures (week of term, number of locations visited, phone use, sedentary time), both anxiety and depression (P<.001) were significantly associated with interest in COVID fatigue. Notably, these behavioral and mental health changes are consistent with those observed around the initial implementation of COVID-19 lockdowns in the spring of 2020. Explore the Full Research

Study #3: In this study, we assess behavioral changes of N=180 undergraduate college students one year prior to the pandemic as a baseline and then during the first year of the pandemic using mobile phone sensing and behavioral inference. We observe that certain groups of students experience the pandemic very differently. Furthermore, we explore the association of self-reported COVID-19 concern with students’ behavior and mental health. We find that heightened COVID-19 concern is correlated with increased depression, anxiety and stress. We evaluate the performance of different deep learning models to classify student COVID-19 concerns with an AUROC and F1 score of 0.70 and 0.71, respectively. Our study spans a two-year period and provides a number of important insights into the life of college students during this period. Explore the Full Research

Study #4: Study 4, as mentioned previously, involves tracking two cohorts of first-year Dartmouth College students over four years, both on and off campus. This initiative has resulted in the most extensive longitudinal mobile sensing study to date. Through the use of passive sensor data, surveys, and interviews, we have documented shifts in behaviors before, during, and following the subsidence of the COVID-19 pandemic. Explore the Full Research

Dartmouth Term Rhythm

We have a hypothesis that there is a signature to the Dartmouth term. That is, if we gave StudentLife to all students at Dartmouth we'd find a common rhythm to the intense Dartmouth term.

We have a hypothesis that there is a signature to the Dartmouth term. That is, if we gave StudentLife to all students at Dartmouth we'd find a common rhythm to the intense Dartmouth term.

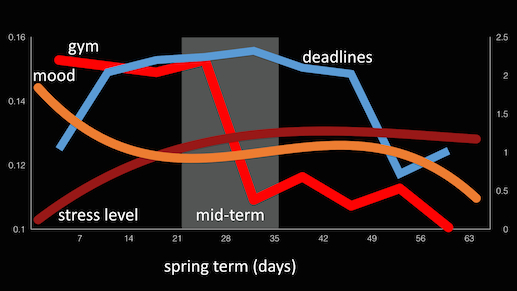

You'll see some examples of the "dart-rhythm" here. Take a look at the paper for more detailed results. The study captured behavioral trends across the Dartmouth term. For example, students returned from spring break feeling good about themselves, relaxed (i.e., low stress levels), sleeping well and going to the gym regularly. That all changed once the Dartmouth term picked up speed toward midterm and finals, as shown in the plot.

The timeline on the right shows conversation frequency and duration across the term. Students start the term by having long (possibly) social conversations. They'd just returned form spring break after all.

The timeline on the right shows conversation frequency and duration across the term. Students start the term by having long (possibly) social conversations. They'd just returned form spring break after all.

As midterm approaches they start having more frequent conversations but they are shorter in length. During midterm week conservation is much more businesslike in comparison to the start of term; that is, students have fewer, shorter conversations. As the term draws to an end things switch around and people have more frequent, longer conservations. Does that sound like your Dartmouth term?

The term starts with students being very active. Strangely enough they don't get much sleep during the first week of term. Why is that? Possibly partying and socializing at the start of term. Class attendance is excellent. As the term gets underway things change. Activity drops sharply to its lowest level during midterm and stays that way for the rest of the term. Sleep follows a similar pattern -- drops to a low point during midterm and then plummets at the end of term. Interestingly enough, class attendance drops off steadily across the term to a low point where students are only attending 25% of their classes on average. Our results also indicate that there is no correlation between class attendance and grade.

The term starts with students being very active. Strangely enough they don't get much sleep during the first week of term. Why is that? Possibly partying and socializing at the start of term. Class attendance is excellent. As the term gets underway things change. Activity drops sharply to its lowest level during midterm and stays that way for the rest of the term. Sleep follows a similar pattern -- drops to a low point during midterm and then plummets at the end of term. Interestingly enough, class attendance drops off steadily across the term to a low point where students are only attending 25% of their classes on average. Our results also indicate that there is no correlation between class attendance and grade.

Predicting GPA from Phones

Many cognitive, behavioral, and environmental factors impact student learning during college. The SmartGPA study uses passive sensing data and self-reports from students’ smartphones to understand individual behavioral differences between high and low performers during a single 10-week term. We propose new methods for better understanding study (e.g., study duration) and social (e.g., partying) behavior of a group of undergraduates. We show that there are a number of important behavioral factors automatically inferred from smartphones that significantly correlate with term and cumulative GPA, including time series analysis of activity, conversational interaction, mobility, class attendance, studying, and partying. We propose a simple model based on linear regression with lasso regularization that can accurately predict cumulative GPA.

The predicted GPA strongly correlates with the ground truth from students’ transcripts (r = 0.81 and p < 0.001) and predicts GPA within ±0.179 of the reported grades. Our results open the way for novel interventions to improve academic performance.

The two plots show when students party and study. This data is automatically inferred by the students’ phones and correlates with the party and study scene at Dartmouth.

This plot shows the partying trends across the complete term. Most partying happens at the start of term and then declines until the spring festival week (called Green Key) then there is little in the way of partying as students buckle down to the end of term and finals.

This is an interesting plot. Class attendance drop after the midterm period but there is an opposite increase in studying? Students are missing classes but studying more.

What's next?

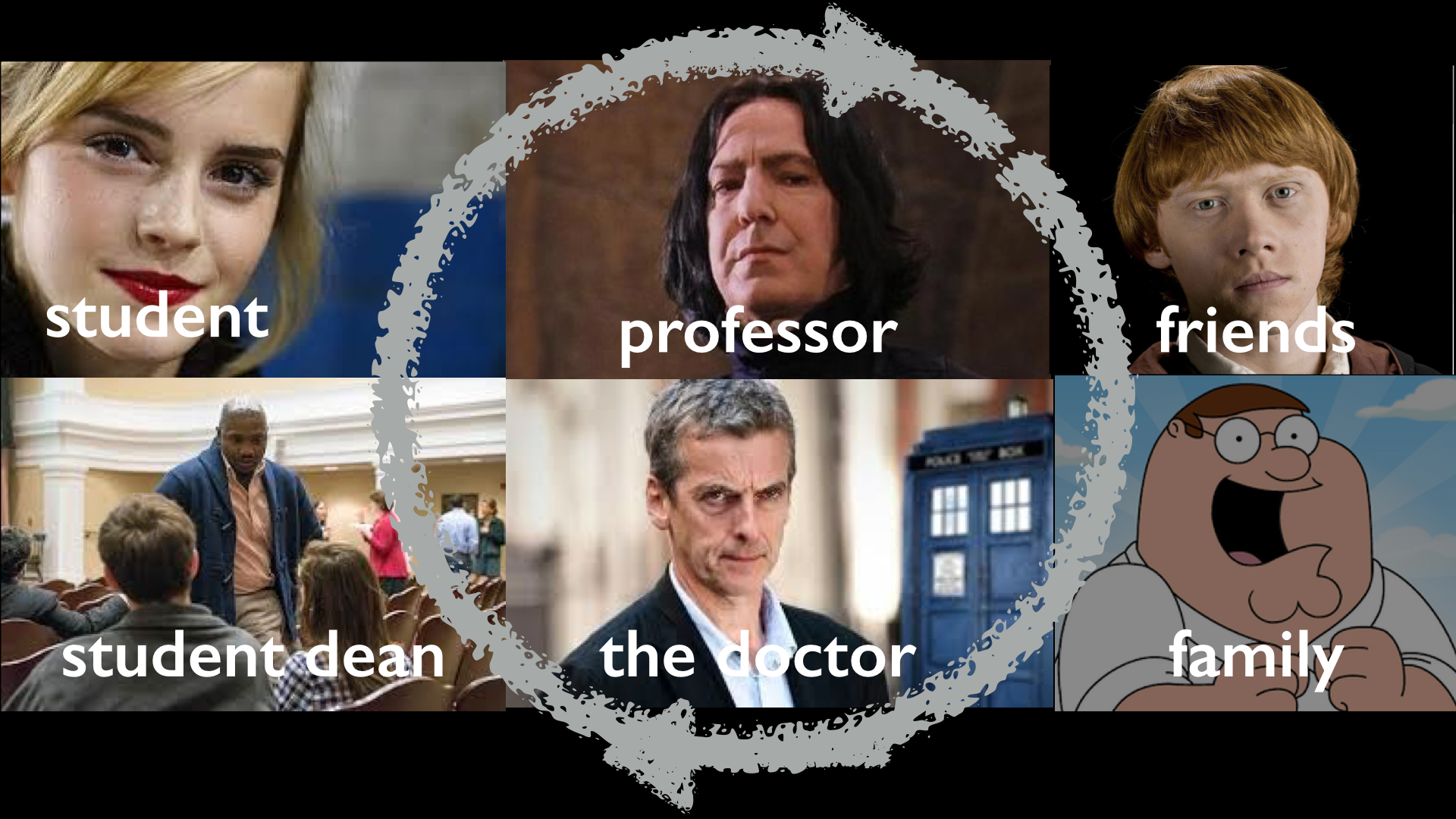

What's next for StudentLife? In a word we want to add intervention to the app. In the future, we hope StudentLife will help students boost their academic performance while living a balanced life on campus.

One could imagine that an app like StudentLife could be used for real-time feedback on campus safety, students at risk; or answer questions like "how stressed is campus right now?" or instead of waiting until the end of term to assess class quality such a tool could give immediate reaction about the quality of teaching at any moment in time. We purposely provided students with no feedback because we didn't want to use StudentLife as a behavioral change tool. We simply wanted to "record" their time on campus. Providing feedback and intervention is the next step. For example, we might inform students of risky behavior; such as, partying too much, poor levels of sleep for peak academic performance, poor eating habits, too socially isolated, not flourishing, struggling, etc.

One could imagine that an app like StudentLife could be used for real-time feedback on campus safety, students at risk; or answer questions like "how stressed is campus right now?" or instead of waiting until the end of term to assess class quality such a tool could give immediate reaction about the quality of teaching at any moment in time. We purposely provided students with no feedback because we didn't want to use StudentLife as a behavioral change tool. We simply wanted to "record" their time on campus. Providing feedback and intervention is the next step. For example, we might inform students of risky behavior; such as, partying too much, poor levels of sleep for peak academic performance, poor eating habits, too socially isolated, not flourishing, struggling, etc.

Get in touch

If you have any questions regarding the study or dataset contact andrew.t.p.campbell [at] gmail [dot] com